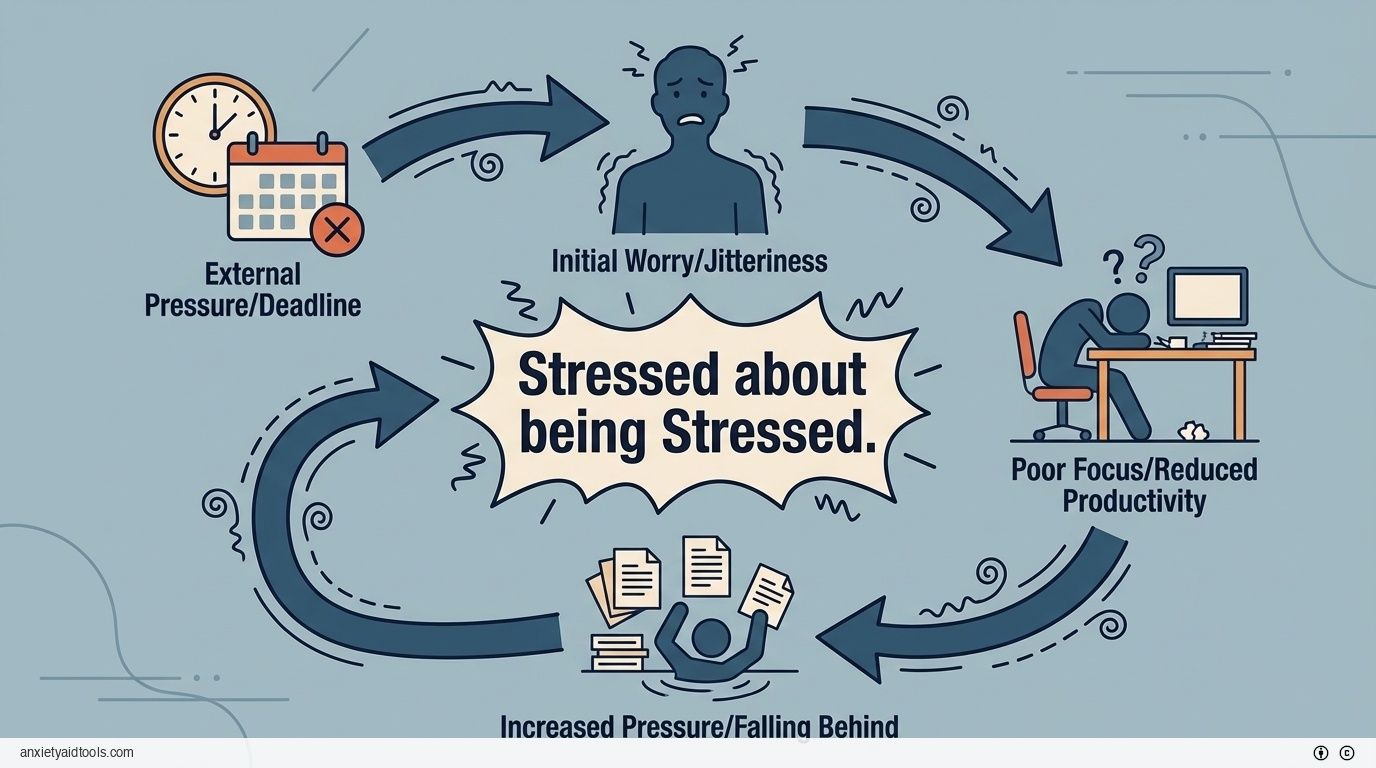

Most of us know the feeling. You wake up with a tight chest or a racing mind, worried about a deadline. That initial worry makes you feel jittery, which then makes it harder to focus. Because you cannot focus, you fall behind, which creates even more pressure. Suddenly, you are not just stressed about the work; you are stressed about the fact that you are stressed.

This is not just a feeling. It is a biological reality. We often treat tension as a temporary state that passes when the weekend arrives. But research suggests that long-term pressure creates a self-sustaining loop. It changes the way your brain functions, making you more likely to feel pressure in the future.

Breaking this pattern requires understanding how it works physically. It is not about "thinking positive" or ignoring the problem. It involves recognizing the mechanical changes happening inside us and using specific, proven methods to interrupt the signal.

The Biological Loop of Chronic Pressure

When we talk about the cycle of stress, we are describing a physical process where the body’s reaction to pressure actually feeds the problem. A large analysis of 95 studies found that dependent stress—stress caused by our own reactions and behaviors—worsens symptoms over time. This creates a situation where past pressure contributes to future pressure, leading to a long-term state of unease 1.

The mechanism behind this is visible in the brain. Chronic unpredictable pressure reduces specific signaling pathways (like mTOR signaling). This reduction leads to changes in the connections between neurons, known as synapses. When these connections weaken, our mental resilience drops. We become less capable of bouncing back from minor annoyances 2.

Changes in Brain Structure

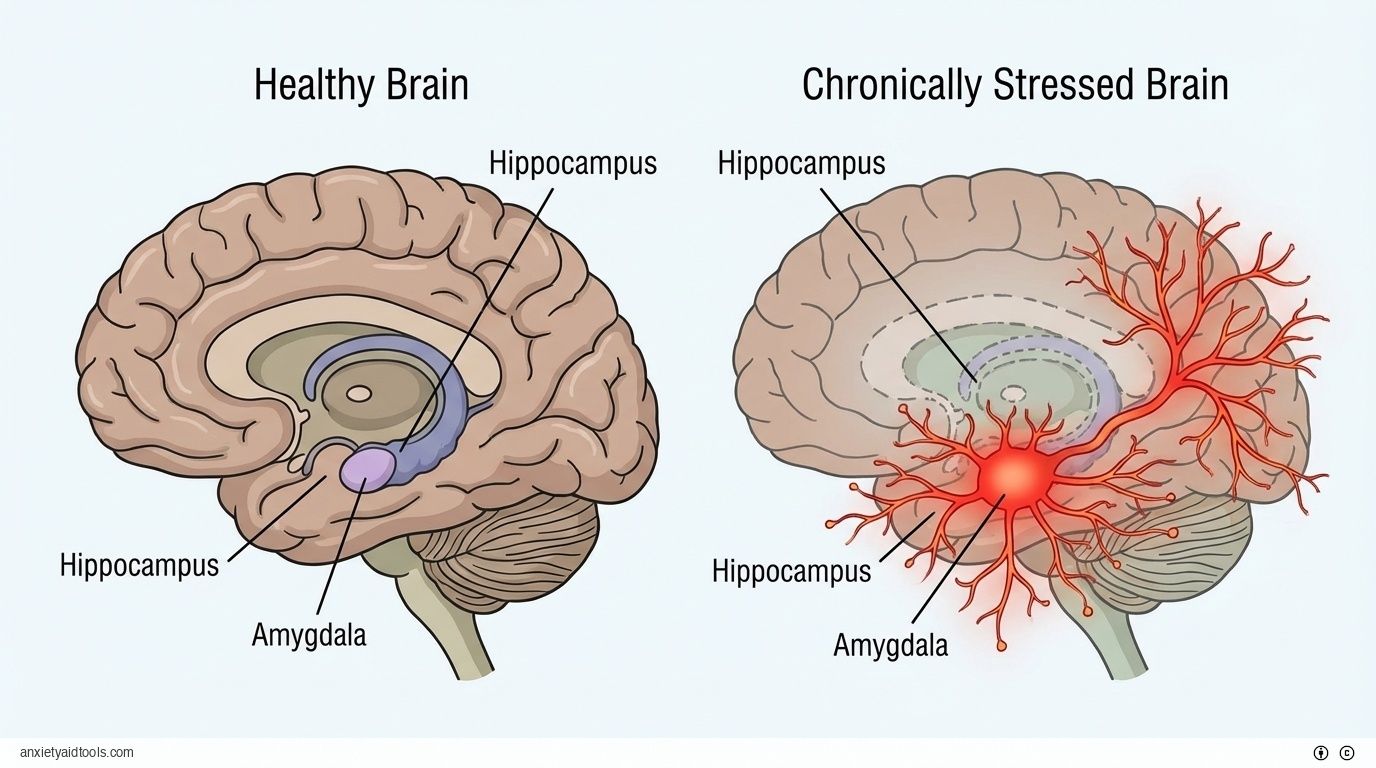

One of the most concerning aspects of this cycle is that it physically reshapes the brain. It is not just a chemical imbalance; it is a structural change.

Research shows that high levels of cortisol—the primary stress hormone—correlate with a reduction in the volume of the hippocampus. This area of the brain helps regulate emotion and memory. In individuals under heavy, sustained pressure, the hippocampus can shrink by 8% to 12% 3.

At the same time, the amygdala—the part of the brain responsible for fear and threat detection—does the opposite. Prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids (stress hormones) causes the dendrites (the receiving branches of neurons) in the amygdala to expand by 15% to 25% 4.

Think of it like a sound system. The part of the brain that calms you down (the hippocampus) loses volume, while the part of the brain that creates alarm (the amygdala) turns up the volume. This structural shift creates a hair-trigger response. You might find yourself reacting with intense worry to situations that used to be manageable. This is not a character flaw; it is a physiological adaptation to a high-pressure environment 5.

The Genetic Component

Our biology also plays a role in how easily this cycle starts. Genetic and epigenetic factors influence how we handle pressure. Studies on gene expression in the brain reveal that chronic tension alters the corticolimbic regions—the areas involved in processing emotion. These changes can flip a switch that makes someone more susceptible to pain and behavioral pressure 6.

This response is not the same for everyone. There are sex-specific differences in how these systems react. For example, research indicates that females may show greater hyperactivity in the amygdala—up to 20% more activation—in response to stressors. This suggests that the biological cost of the cycle can vary significantly depending on the person 7.

The Physical Cost on the Body

The brain is not the only victim of this loop. The "stress of stress" wears down the body’s other systems, creating physical problems that often lead to more worry.

Immune System Suppression

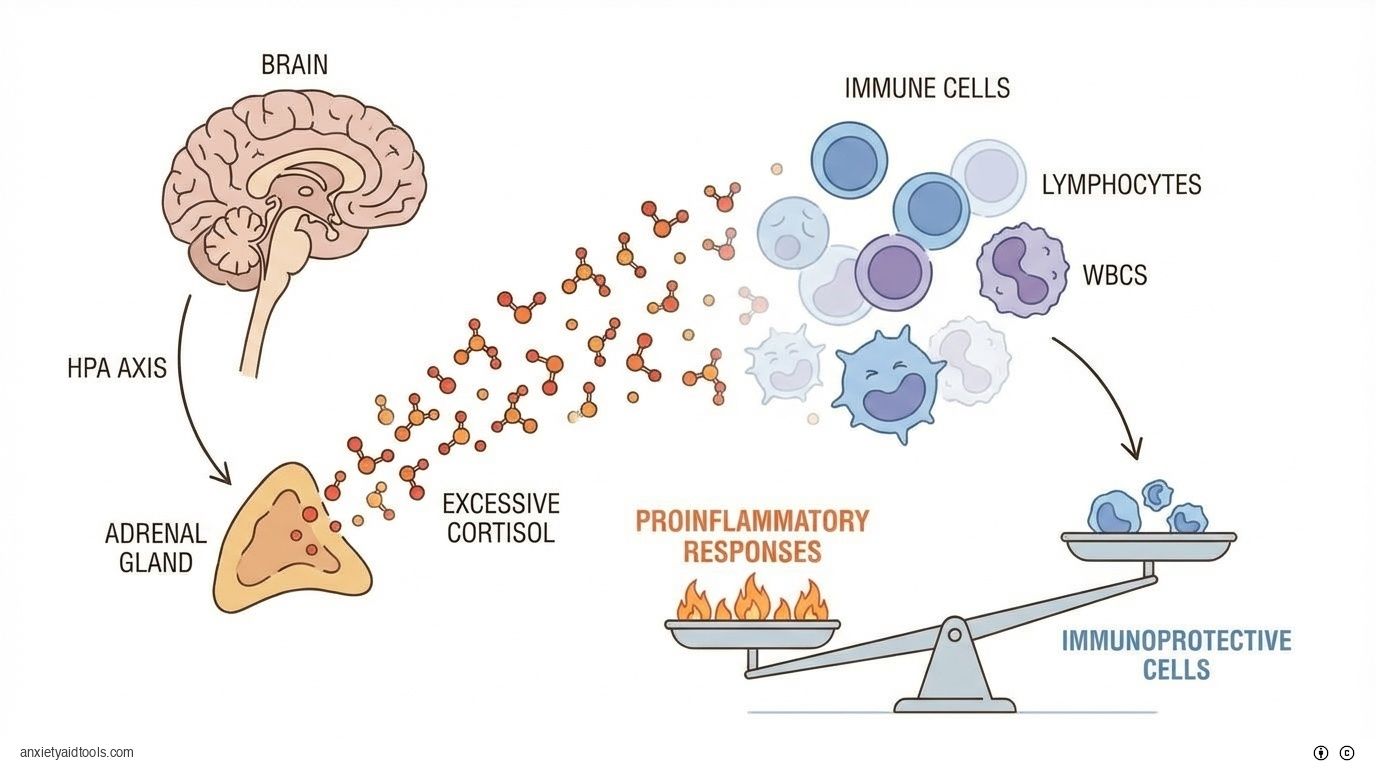

You might notice that you get sick more often after a major project or a difficult personal event. This happens because long-term pressure suppresses immune function. It disrupts the balance of cytokines—proteins that help cells signal each other.

Under chronic pressure, the number of immunoprotective cells and their movement can drop by 20% to 30%. This leaves the body open to infections. The body produces fewer Type 1 cytokines, which are needed to fight off viruses and bacteria 8.

The HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) releases cortisol, which normally helps manage inflammation. But when cortisol levels stay high for too long, the system stops working correctly. Lymphocyte proliferation—the growth of white blood cells—can drop by 15% to 25%. This weakens the body's defense system significantly 9.

In a strange twist, while the body becomes worse at fighting outside threats, it can become too aggressive against itself. The imbalance can lead to a dominance of proinflammatory responses, which may worsen autoimmune conditions 10.

Cardiovascular Strain

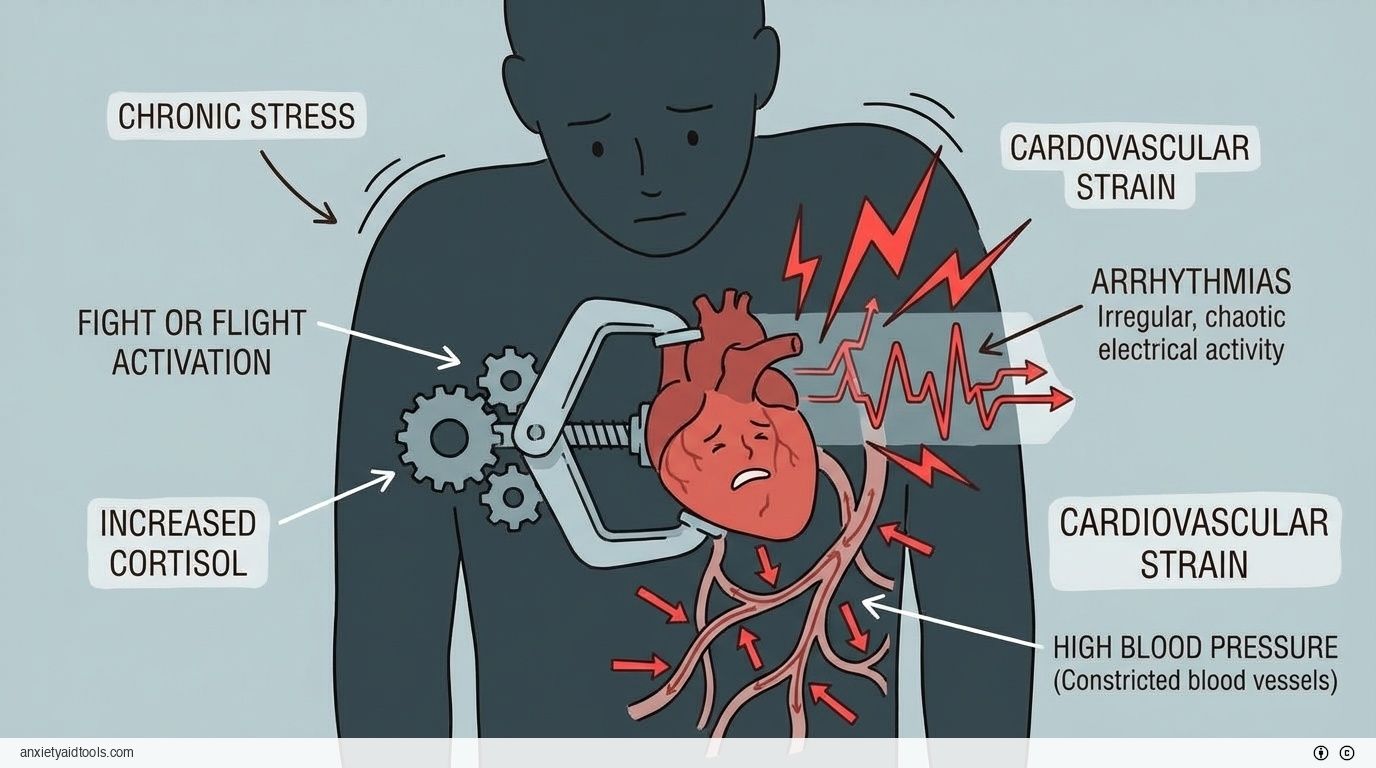

The heart takes a heavy hit from this cycle. The connection between the brain and the heart is direct. When the corticolimbic areas of the brain are dysregulated by pressure, they send chaotic signals to the autonomic nervous system.

Meta-analyses show a clear link: populations under high pressure face a 1.5 to 2.0 times higher relative risk for coronary heart disease 11. The incidence of cardiovascular events is 20% to 30% higher in these groups. This happens because the "fight or flight" system stays active, causing dysfunction in the lining of the blood vessels and making arterial plaques more unstable 12.

Even in adulthood, chronic tension triggers physical changes. It lowers the threshold for arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) and causes sympathetic surges that can raise blood pressure by 15 to 25 mmHg. If a person experienced difficulty in childhood, these risks compound through epigenetic alterations 13.

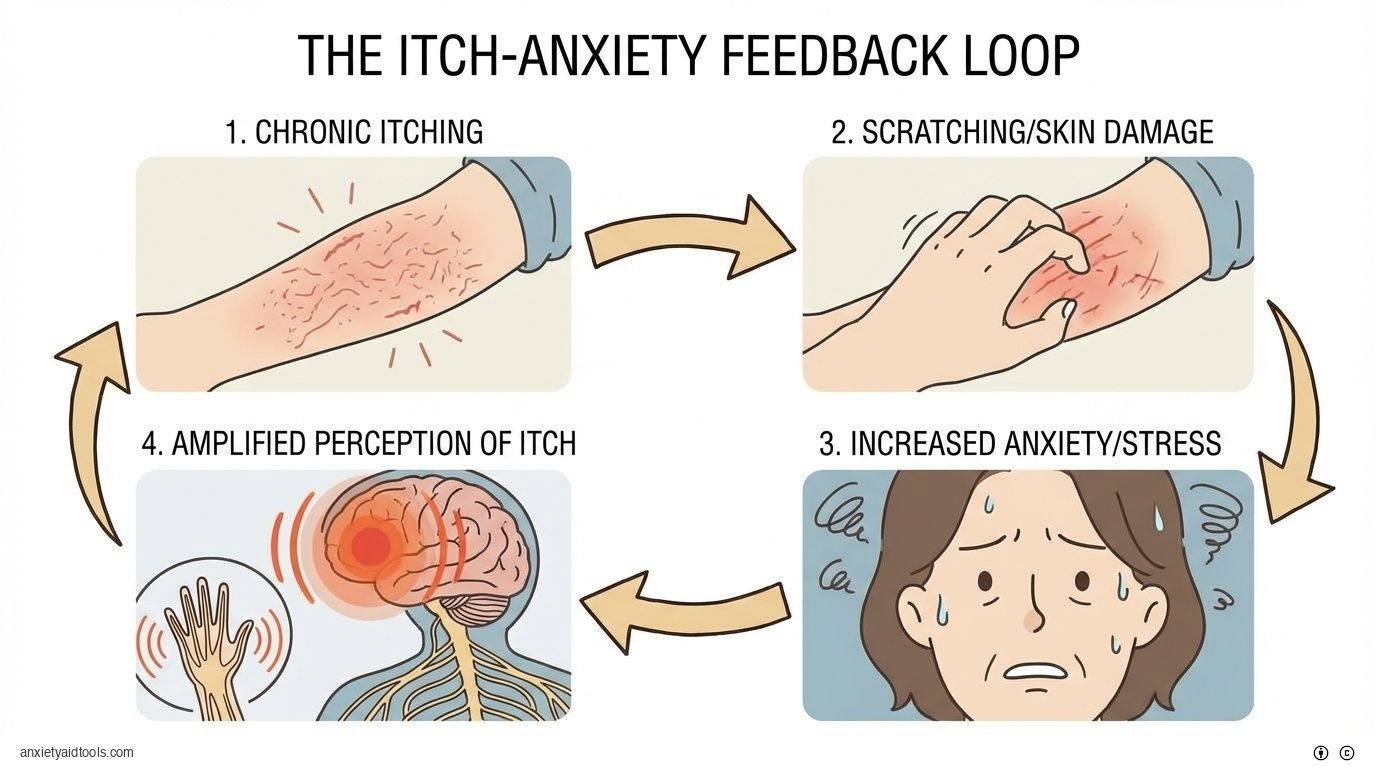

The Itch-Anxiety Example

To understand how the cycle feeds itself, we can look at a specific physical symptom: itching. It sounds minor, but it perfectly illustrates the loop.

Chronic itching sensitizes the pathways in the nervous system. The more you itch, the more you scratch. The scratching relieves the itch for a second but damages the skin and creates anxiety. The amygdala gets involved, and the stress of the situation amplifies the perception of the itch by 25% to 35%. This is common in conditions like atopic dermatitis. You feel stressed, so you itch more. You itch more, so you feel more stressed. The cycle creates its own momentum 14.

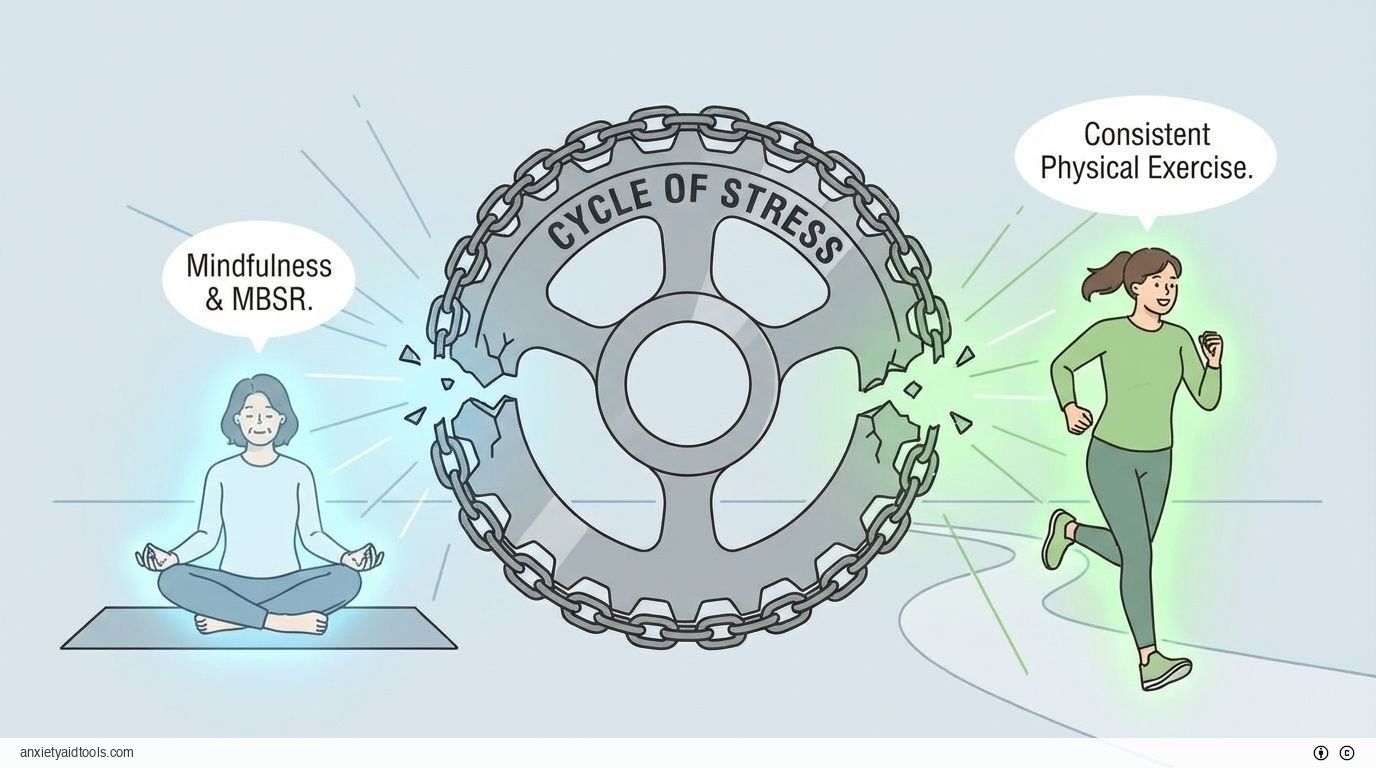

Breaking the Pattern with Action

Understanding the biology helps us see why "just relaxing" is rarely enough. We need interventions that actually change the biological signals. Fortunately, several methods show strong evidence for interrupting this loop.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness is often discussed as a vague concept, but the data on it is concrete. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) are structured programs that have shown measurable effects.

In a review of 115 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 8,000 participants, these interventions reduced stress with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d of 0.51). They also improved anxiety (d=0.49) and low mood (d=0.37) compared to people who were just on a waiting list 15.

This works for healthy people too, not just those with clinical diagnoses. Daily practice over 4 to 8 weeks can improve quality of life and reduce general tension. The key is consistency. The brain changes we discussed earlier—like the shrinking hippocampus—take time to develop, so reversing the trend also takes time 16.

For professionals dealing with burnout, these interventions are highly effective. Studies on physicians found that mindfulness programs reduced symptoms of emotional exhaustion by 20% to 30%. Interestingly, established, structured versions of these programs tended to outperform simple apps, suggesting that the depth of the practice matters 17.

The Role of Physical Exercise

If sitting still and observing your thoughts feels impossible, physical movement is an equally valid exit ramp from the cycle.

A 5-week study comparing daily physical exercise to mindfulness meditation found that both were effective—but you have to do the work. Young adults who exercised at least 70% of the prescribed time saw improvements in attention control and executive functioning.

More importantly, the exercise group reduced worrying by 15% to 20%. By forcing the body to exert energy, you help the brain build cognitive resilience. This improves your ability to focus and make decisions, which addresses the "I can't focus" part of the stress loop 18.

Interrupters for Physical Symptoms

For those suffering from physical pain or discomfort tied to tension, addressing the mind can help the body.

In people with chronic low back pain, MBSR improved physical function. At 8 weeks, participants showed better movement and less disability. This suggests that by disrupting the mental aspect of the pain-stress cycle, the physical limitations became less severe 19.

Similarly, for patients with vascular disease, mindfulness training decreased anxiety levels significantly. While it did not always change blood pressure numbers immediately, it lowered the psychological burden, breaking the link between the disease and the emotional distress it causes 20.

Moving Forward

The cycle of stress is formidable because it is biological. It recruits your genes, your brain structure, and your immune system to keep the wheel turning. But it is not a permanent sentence.

The data shows that we can reverse these effects. We can restore synaptic function. We can lower the volume of the amygdala. We can improve our immune response. It requires treating the pressure not as a personality trait, but as a mechanical issue that needs a mechanical solution.

Whether through structured attention training or consistent physical exertion, the goal is the same: to send a different signal to the brain. Once that signal changes, the body follows. The loop breaks, and the recovery begins.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does chronic stress affect the hippocampus?

What is the difference between MBSR and MBCT for stress management?

Can physical exercise really reduce worry and anxiety?

How does the amygdala change under chronic stress?

Does stress suppression of the immune system lead to more infections?

How long does it take for mindfulness practice to show results?

What is the connection between stress and cardiovascular disease?

Can addressing stress help with chronic physical pain?

Footnotes

- Rnic K, Santee AC, Liu H, Chen RX, Machado DA, Starr LR, Dozois DJA. The vicious cycle of psychopathology and stressful life events: A meta-analytic review testing the stress generation model. Psychol Bull. 2023 May-Jun;149(5-6):330-369. doi: 10.1037/bul0000390. PMID: 37261747. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37261747/ ↩

- Bath KG, Russo SJ, Pleil KE, Wohleb ES, Duman RS. Circuit and synaptic mechanisms of repeated stress: Perspectives from differing contexts, duration, and development. Neurobiol Stress. 2017 May 6;7:137-151. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.05.001. PMID: 29276735. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29276735/ ↩

- Roberts BL. Brain-body responses to chronic stress: a brief review. Fac Rev. 2021 Dec 16;10:83. doi: 10.12703/r/10-83. PMID: 35028648. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35028648/ ↩

- Sheela Vyas, Francois Tronche, Nuno Sousa. Chronic Stress and Glucocorticoids: From Neuronal Plasticity to Neurodegeneration. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6391686. doi: 10.1155/2016/6391686. PMID: 27034847. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27034847/ ↩

- Bruce S McEwen. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007 Jul;87(3):873-904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. PMID: 17615391. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17615391/ ↩

- Eric J Nestler, Stephen G Waxman. Resilience to Stress and Resilience to Pain: Lessons from Molecular Neurobiology and Genetics. Trends Mol Med. 2020 Oct;26(10):924-935. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.03.007. PMID: 32976800. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32976800/ ↩

- McEwen BS. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2017 Jan-Dec;1:2470547017692328. doi: 10.1177/2470547017692328. PMID: 28856337. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28856337/ ↩

- Firdaus S Dhabhar. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res. 2014 May;58(2-3):193-210. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0. PMID: 24798553. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24798553/ ↩

- Alotiby A. Immunology of Stress: A Review Article. J Clin Med. 2024 Oct 25;13(21):6394. doi: 10.3390/jcm13216394. PMID: 39518533. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39518533/ ↩

- Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(5):300-17. doi: 10.1159/000216188. PMID: 19571591. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19571591/ ↩

- Viola Vaccarino. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024 Sep;21(9):603-616. doi: 10.1038/s41569-024-01024-y. PMID: 38698183. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38698183/ ↩

- Andrew Steptoe. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012 Apr 3;9(6):360-70. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. PMID: 22473079. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22473079/ ↩

- Kivimäki M, Steptoe A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018 Apr;15(4):215-229. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.189. PMID: 29213140. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29213140/ ↩

- Kristen M Sanders, Akihiko Ikoma, Gil Yosipovitch, et al. The vicious cycle of itch and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018 Apr;87:17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.009. PMID: 29374516. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29374516/ ↩

- Gotink RA, Chu P, Benson H, Fricchione GL, Hunink MG. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 16;10(4):e0124344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124344. PMID: 25881019. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25881019/ ↩

- Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2015 Jun;78(6):519-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. PMID: 25818837. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25818837/ ↩

- Johannes C Fendel, J.J. Bürkle, A.S. Göritz. Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Reduce Burnout and Stress in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad Med. 2021 May 1;96(5):751-764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003936. PMID: 33496433. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33496433/ ↩

- Esther I de Bruin, J Esi van der Zwan. A RCT Comparing Daily Mindfulness Meditations, Biofeedback Exercises, and Daily Physical Exercise on Attention Control, Executive Functioning, Mindful Awareness, Self-Compassion, and Worrying in Stressed Young Adults. Mindfulness (N Y). 2016;7(5):1182-1192. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0561-5. PMID: 27642375. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27642375/ ↩

- K Soundararajan, V Prem. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on physical function in individuals with chronic low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2022 Nov;49:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101623. PMID: 35779457. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35779457/ ↩

- Abbott RA, Whear R, Rodgers LR, Bethel A, Thompson Coon J, Kuyken W, Stein K. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Psychosom Res. 2014 May;76(5):341-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.012. PMID: 24745774. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24745774/ ↩